Branching out: Designing an Art Scholarship Curriculum

Saara Karppinen

MEL23 December 2023

Curriculum Design and Implementation

Acronyms used:

KS3- Key stage three, a ‘phase’ of learning for students aged 11-14, which includes years 7-9. Art education is compulsory at this stage.

KS4- Key stage four, students aged 14-16, years 10 and 11. Students must choose their subjects, creating a specialised curriculum.

ASC- Art scholarship curriculum

Ofsted- Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills.

Introduction

I will be planning a curriculum for the art scholarship programme that I am developing for KS3 students. Students have applied to take part in this programme, at it will take place during lunch times and some lesson times over the school year. It will run in parallel to the compulsory art lessons for this age phase. In order to plan and diagnose what will be addressed in this curriculum, I will first consider what is already being offered, what is missing, and what theory can guide the formation of this curriculum. Lastly, I will consider the practical implementations. For context, this is for Trinity Church of England secondary school, a local authority school in London, for students aged 11-16. The art scholarship programme offers 20 places for students who wish to take part in art outside of lessons, and want something more involved then the ‘drop in’ extracurricular activities offered.

Context

Current ‘curriculums’ in place

Students at the setting learn the national curriculum at KS3, and at KS4 if they choose art as a subject, they continue to do the AQA fine art course. The national curriculum outlines that students should learn drawing and painting, and there is a focus on developing competency in skills and art analysis (‘National Curriculum in England’)The following statement makes the majority of the national curriculum, there is no set delivery or content.

Pupils should be taught to develop their creativity and ideas, and increase proficiency in their execution. They should develop a critical understanding of artists, architects and designers, expressing reasoned judgements that can inform their own work. (‘National Curriculum in England’)

Trinity has developed a school wide statement and plan for how all subjects are to deliver their curriculum, which has been underpinned by the idea of mastery, cognitive load theory and the delivery is largely based on Rosenshine’s principles of instruction. (Rosenshine) The aims of the institution, in following a self-declared ‘traditional’ and ‘academic’ curriculum have impacted the formation of the art curriculum at the school.

At Trinity we believe in a traditional academic curriculum, the intent of which is ambitious in content and consistently high quality in its implementation, resulting in the desired impact of excellent outcomes for pupils. (Trinity School)

In response, I wrote a curriculum in 2021 that echoed the requirements of the institution, and based the structure of learning on the pedagogy that was being adopted in the school. The intent in the curriculum is to closely follow the agenda and set objectives from the institution and national curriculum.

With a focus on painting, drawing, and printmaking, we deeply believe that mastery over a few specific skills is more challenging and ambitious then a superficial attempt at many. This underpins all teaching at Trinity, as all year groups develop using the same media, but with a varying range of mastery and techniques. (Karppinen)

The national curriculum is brief on it’s requirements, and is practical in the provision that should be offered. The National curriculum offers a basic framework, and the subject leader has the autonomy on how learning is to be delivered. However, as a subject leader, I experience pressure to deliver outcomes, as the English education system uses a lot of accountability measures. This has an hidden impact on the structure of the curriculum. As a result, the KS3 curriculum is largely structured to prepare students for the KS4 curriculum, where students take nationalised exams which generate data which has a significant impact on the schools reputation, and often the career of the teacher. The culture of accountability is generating a curriculum which is focussing on students demonstrating specific high level skills to secure outcomes.

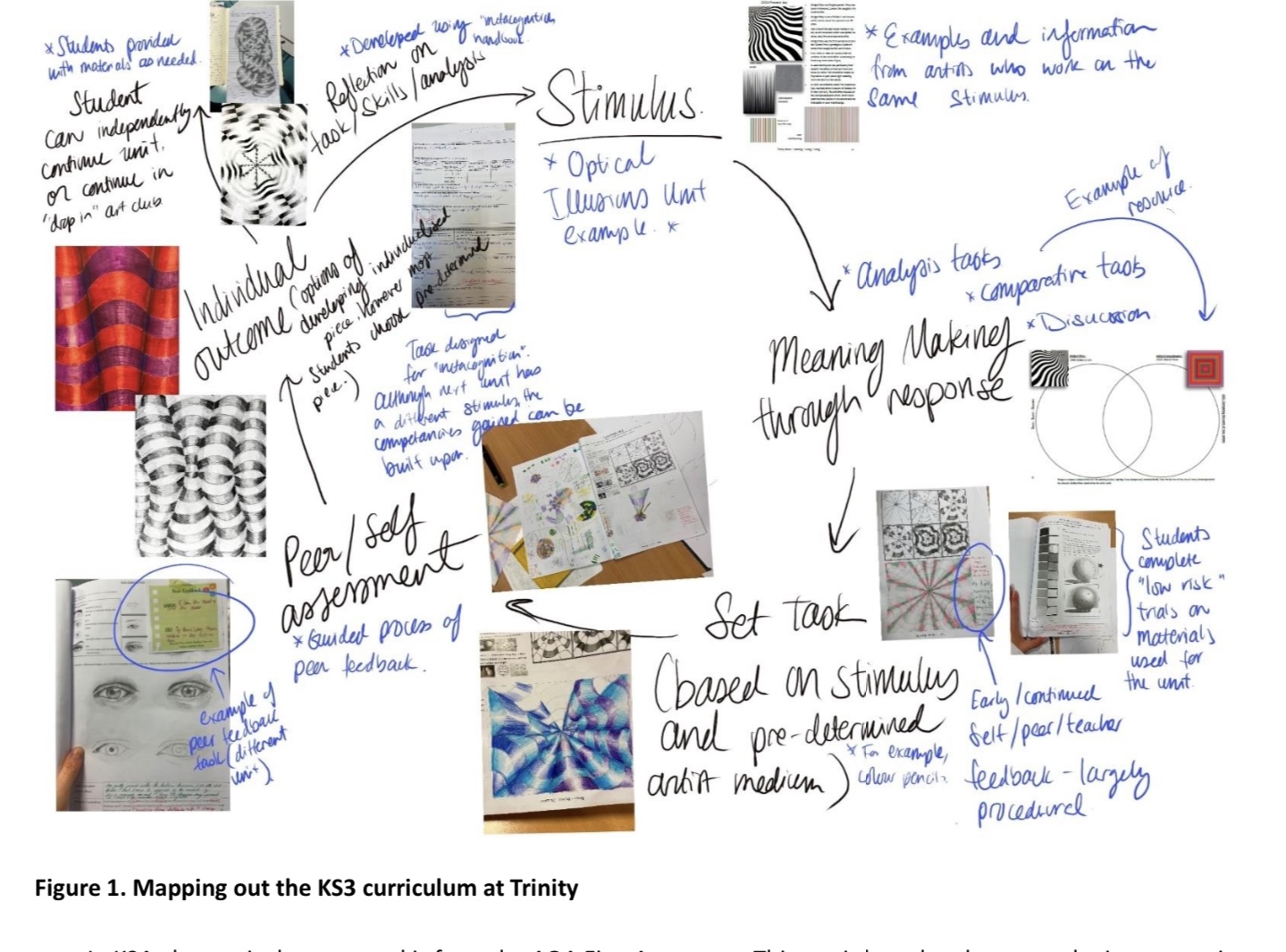

To demonstrate the structure of learning, and the stages of how the learning is structured, I have mapped out an example of a KS3 and KS4 unit of work. This is an example of how the national curriculum is implemented at Trinity Church of England school. The more detailed curriculum statement is in the appendix.

Firstly, the KS3 unit starts with a ‘Stimulus’, in this example, it is the introduction to the ‘Op Art’ artist Bridget Riley. Lessons are structure to develop meaning making by forms of analysis and comparison tasks, followed by tasks set by the teacher to develop ‘practical skills’ which enable the student to eventually create an outcome inspired by the artist studied. As a process, this ongoing self and peer assessment which is structured by the teacher, and students are encouraged to plan some individual outcomes (although it is more popular for students to choose a previously practiced outcome) as a ‘final piece’, a realised outcome that shows the development of competencies from the unit. This concludes with a reflection and assessment. The overall structure of this curriculum was based on gradual release, based on Rosenshines principes of instruction. (Rosenshine) As students complete set tasks, they will gain confidence, and scaffolds to tasks can be gradually lessened so that students develop mastery to complete challenging tasks independently. In this way, students complete planned ‘Op art tasks’ with direct instruction from the teacher, and are able at the end of the unit to ‘proficiently’ produce a op art drawing without the teachers support. This is the process for teaching and learning which is expected of teachers at this institution.

Figure 1. Mapping out the KS3 curriculum at Trinity

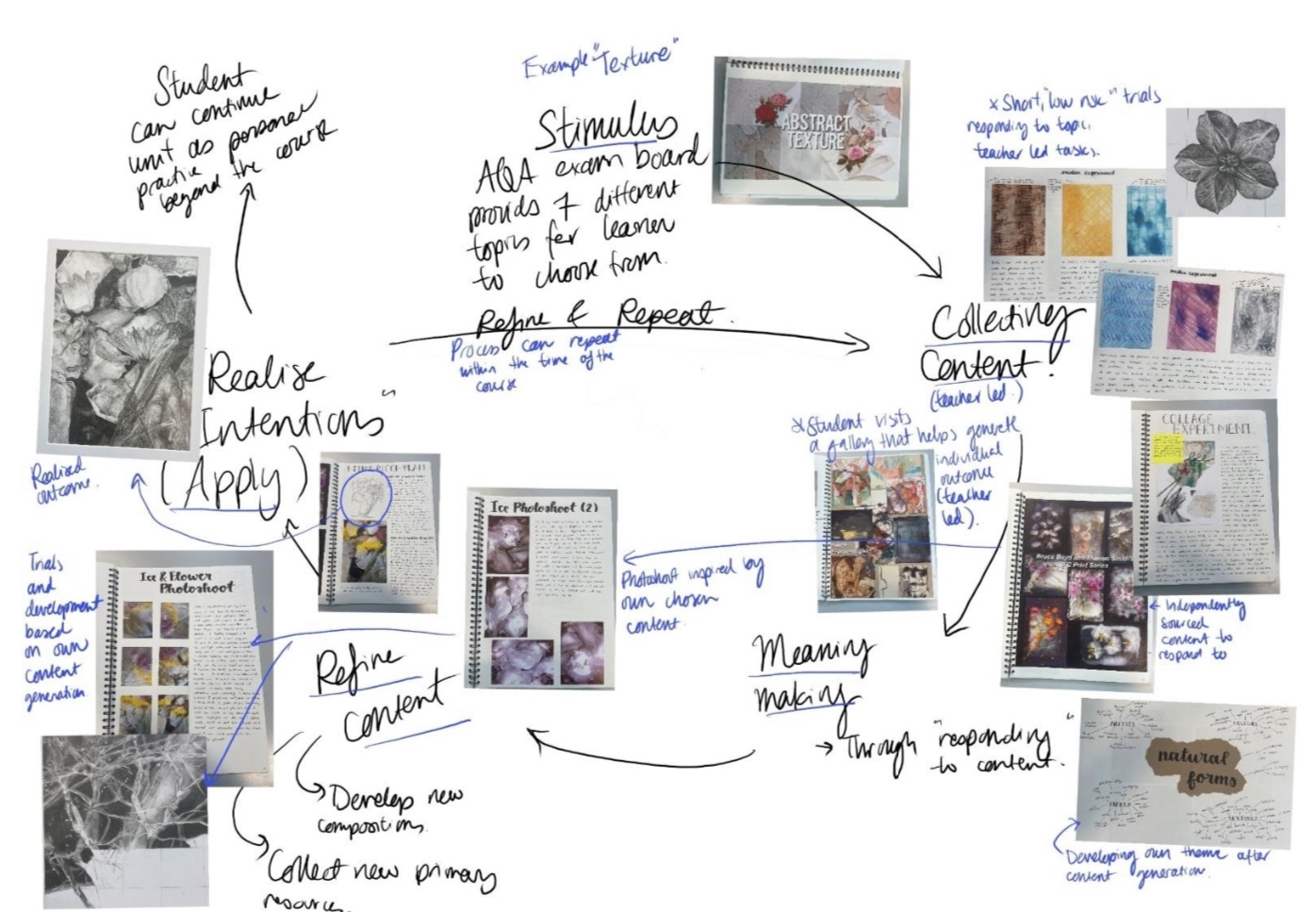

In KS4, the curriculum covered is from the AQA Fine Art course. This too is broad and open to the interpretation of the subject lead at any institution (AQA), however success in delivering the course is determined by nationalised assessment, which too is contributing to a ‘hidden curriculum’ of pushing skills and techniques that will achieve easily understood ‘high outcomes’. Similarly, this starts with a stimulus, in this example, the topic of ‘texture’. The student experiences short, teacher led tasks and collects artist/references that inspire them in this topic. I have roughly called this stage ‘collecting content’. Following from this, students analyse the work of artists, or make small trials based on the collected content, I have called this stage ‘meaning making’. The learner is making connections between a wide range of found sources, and is starting to make their own choices about what to use in their unit. The next stage I have called ‘Refine Content’ where students make decisions about what extended pieces to make based on shorter trials. For example, the student in the example below has refined their project by focussing on completing drawings of flowers in ice, in the refine stage they have completed a photoshoot to plan for their extended piece. Students then have a 10 hour assessed period, where the extended outcome is completed, or students who achieve this stage earlier can repeat the process and further develop and delve into their chosen topic.

Figure 2. Mapping out the KS4 Curriculum at Trinity

In breaking down what students are experiencing in lessons, there is a clear difference and leap between students autonomy from KS3 to KS4. All KS3 units have roughly pre-determined outcomes, and students have no agency to decide what to pursue. The KS4 curriculum is structured to allow for choice to be made, however, learning is very individual. The main feedback in KS3 is student led and structured peer feedback tasks, whereas the KS4 student mostly has brief dialogues with the teacher and unless they have develop a sense of community in the classroom, they do not benefit from peer feedback. Learning moves from being driven forwards by the classroom community to an individual process as agency increases.

The current extra-curricular provision in the school is a ‘drop in’ art club, in which students can come and continue their work from lessons and benefit from being in a more social setting to continue their work.

Requirements of setting

The national curriculum is brief on it’s requirements for art education at KS3, however the implementation of the curriculum is determined by the curriculum policy at the institution, and guided by the hidden curriculum which is the need for high achieving scores at KS4. This year, Ofsted released a research review of what art teaching should look like from the perspective of the Department for Education. This review broke down the areas of learning into three domains of knowledge, which are practical (regarding developing proficiency), theoretical (cultural and contextual content), and disciplinary knowledge (what pupils learn about how art is studied) (‘Research Review Series’). Similarly to the curriculum intent at Trinity school, this research review bases the curriculum on theories of cognitive science, and values a reduced curriculum in favour of ‘mastery’, as noted:

‘While pupils will not be able to engage meaningfully in each tradition if the curriculum is ‘a mile wide and an inch deep’, the various components that pupils are taught through the curriculum are, nonetheless, what give them a broad and accurate conception of drawing, painting, and sculpture’ (‘Research Review Series’)

The other curriculums…

The reason for addressing the curriculum in place at the school, is that this will give the foundation for what I would like the ‘art scholarship’ curriculum to address. The art scholarship programme is not tied to the lesson structure requirements of the institution, there is an opportunity to develop a unique programme, that supports the national curriculum but is not tied to it. In my analysis, I was drawn to what the students are learning through the hidden curriculum and null curriculums that have developed in response. (Wilson). It would be redundant to offer the students more of what they are already experiencing in lessons, quite simply, it is not what they have signed up for, although it would be easiest to deliver.

Hidden Curriculum

Some sources have noted that there is a disconnect between what education policy is driving curriculum towards, and what art education theory would have as examples of best practice in developing curriculum. Walton notes, that the drive towards tailoring education towards ‘the cognitive science conception of knowledge as information processing is especially prominent in education policy’ (Walton). The disconnect happens when academics are writing specifically at art education, Walton argues that there is a middle ground. The Ofsted recommendation noted, ‘The vastness, plurality and richness of the subject can sometimes present challenges for subject leaders and curriculum planners’ (‘Research Review’), indicating that the nature of the subject is challenging to pin down to a set of processes, and could be further analysed as an interesting statement to end a review of best practice on. The hidden curriculum (Owen Wilson) at Trinity places an emphasis of mastery of a predetermined set of skills, although it is not the intention of the curriculum, the lack of breadth of mediums and artists covered is teaching the students that if they are not proficient in these mediums, they are not deemed to be successful in the subject. Students are assessed in KS3 based on ‘age related expectations’, which is not the assessment terminology for KS4, which instead uses the language of ‘moderate/consistent/highly developed’. When writing about assessment in the national curriculum, Atkinson noted that the use of banding students achievement based on what a ‘average’ drawing should look like is teaching students a limited view of what could be. The example he highlights is the assessment of a drawing- the teacher will determine what skills should be demonstrated, and expects a student who is proficient to mirror this expectation- Atkinsons argument is that this is antithetical to art education as a whole, differences is perception and expression should be possible, but when we use national guidelines and a national curriculum to set our expectations, we teach students that differences in perceiving are not accepted. (Atkinson)

‘Under the gaze of pedagogic discourses and practices pupils’ abilities become visible, are constituted, sanctioned or corrected.’ (Atkinson)

The emphasis of ‘accuracy’ which is further enabled by the focus on mastery (,as for mastery you have to have ‘inaccurate’ methods,) and student work being marked as working towards/at/exceeding standard, forms the hidden curriculum of allowing only limited forms of work to be considered ‘successful artworks’. If you have ‘successful artworks’, you will have successful artists, and at the same time, ‘unsuccessful artists’.

Aims and Principles for art scholarship curriculum.

After having outlined what is already being offered in the curriculum in art lessons, I can start to consider what should be offered alongside this. In this section I will outline what theory will underpin the new ‘art scholarship’ curriculum. Another challenge here is what should be taught in art? What I will consider is what kind of behaviours will enable students to be ‘creative’, and help students make their own connections and meanings to art. When talking about creativity, various dictionaries note that creativity is related to the act of ‘creating’, and making original decisions. Neither the national curriculum, or the Ofsted review touch on the idea of creativity in the sense that this requires agency, as to make a decision agency is required. However, the concepts of ‘Art’ and ‘creativity’ are inexplicably linked, however not explicitly addressed in the national curriculum. To add some clarity, I will define visual art as visualising decision making. This could be as straight forwards as the decision of creating a realistic copy of another artist work, or creating and developing a composition based on trying to visualise a concept, or perhaps the choice to not create a visual outcome. Thus my own personal aim as an art teacher becomes to enable an environment where students can make decisions, and help fulfil the requirements for the realisation of these ‘decisions’.

In this art scholars curriculum, I would like to encourage creativity, and in order to understand how to address this, I will consider this as opportunities to make or disregard choices.

Subjectification and art education

When regarding Biesta’s three domains of education, qualification (developing skills and knowledge), socialization (engaging in social and pollical practices), and subjectification (understanding and engaging with autonomy) (Biesta) the qualification domain is being covered in the lessons already occurring, student are gaining practical skills and competencies, and the department is achieving a high progress score nationally. The KS3 art curriculum does not specifically develop is the subjectification domain. It is also my understanding that there is a link between engaging in autonomous acts and ‘creativity’, if I can create a space where students can develop their sense of autonomy, it stands to reason they will be enabled to make more ‘creative’ choices in their art work, and that this could in the long run support their development as artists. Walton writes about the role of authority a student has over their artwork:

One way of thinking about the purpose of art and design education is to say that we would like students to become authoritative about aspects of the field, to take on commitments to the inferential integration of concepts and practice that constitute knowledge in the subject. This acquired authority and ownership can be manifested in a variety of roles. One, but only one, version of this might be the authority of the artist over, responsibility for and responsibility to, her own work. ((Walton, ‘Anton Ehrenzweig, the Artist Teacher and a Psychoanalytic Approach to School Art Education’))

For me, the connection between students making decisions is an act of genuine autonomous behaviour, and links to the subjectification domain. Through art education, students should have the opportunity to develop their understanding of themselves, and choices to make decisions at all scales. The ASC will by design aim to provide students with the opportunity to make or choose different avenues to explore their creative outputs.

Intentionally developing a community

Rhizomatic learning, connectivism, and reading on the meaning making framework has grounded the idea that the new curriculum for the art scholars needs to consider how to enable this group as a community. For the art scholars to be able to engage with personal choice, there needs to be a welcoming environment for this to happen. Rhizomatic learning, where learners bring their own context and develop meaning making by connecting to their own context is an answer on how to build this. The following quote from Cormier has guided this process:

It (rhizomatic learning) overturns conventional notions of instructional pedagogy by positing that “the community is the curriculum”; that learning is not designed around content but is instead a social process in which we learn with and from each other (Cormier, Rhizomatic Learning | Advance HE).

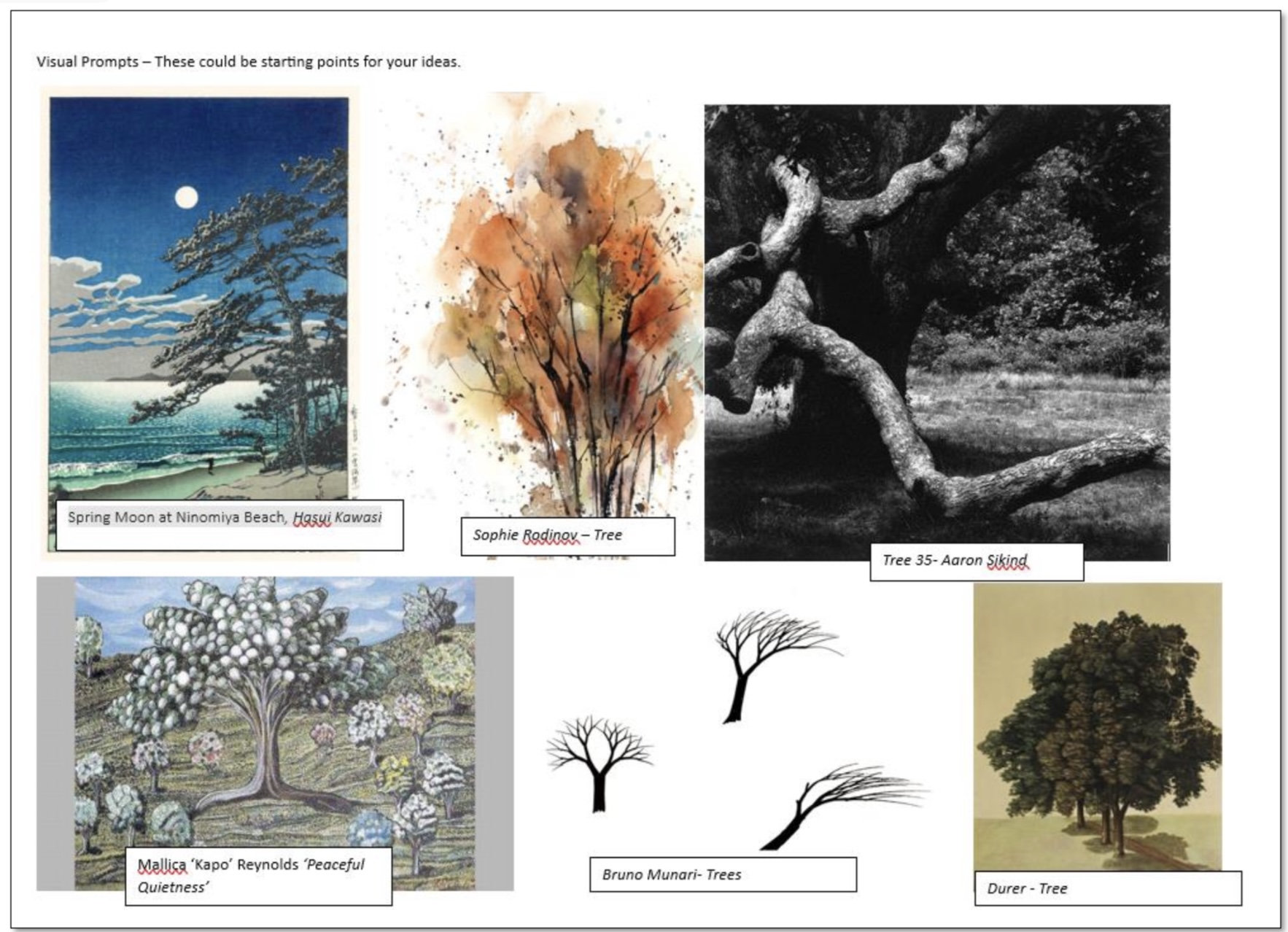

For this process of learning to happen, learners will need to actively share and listen to each other and the context they bring to the sessions. This may be challenging, as this is not a priority in the overall curriculum, so it may be a new experience. I will enable this by building small tasks where students can bring in ideas, and ensuring that this is a easy process to engage with. I do not want to create ‘more responsibility’, by creating an expectation, so instead I will allow time, but also resource for students to use to bring their own understanding of the unit to the community of learners. For example, for a unit ‘trees’, I will start the conversation by learners bringing examples of images of trees to the following session, but in order to make this a choice not an expectation, I will also provide visual resources of trees that learners can present and justify as their choice. It will then me the vocalization of why a particular image a student has chosen, where they share their context with the community. The aim is for students to learn through the community, starting with the guide of simple tasks of collecting and sharing artifacts.

The ideas in connectivism will also be used in forming this curriculum. Students already have concepts and meaning that they can bring to this community, it is not the teachers role in this space to bring meaning in, but to enable this community to make the connections and find the meanings– the learner's challenge is to recognize the patterns which appear to be hidden. The collection of content/artifacts and discussion on this process will develop meaning-making, ‘Meaning-making and forming connections between specialized communities are important activities.’ (Siemens)This idea of meaning making by forming connections has also been explored in texts that are concerned with responding to gallery and museum exhibits.

Enabling Meaning making

The ideas of rhizomatic learning and connectivism lend themselves to texts regarding individuals learning together from joint experiences of visiting museums/galleries. Pringle state that from this experience, ‘individuals learn together, generating knowledge and understandings they would not achieve alone.’ (Pringle). By discussing an experience of viewing art fist hand, dialogue can be a tool that learners use to connect personal content and create meaning.

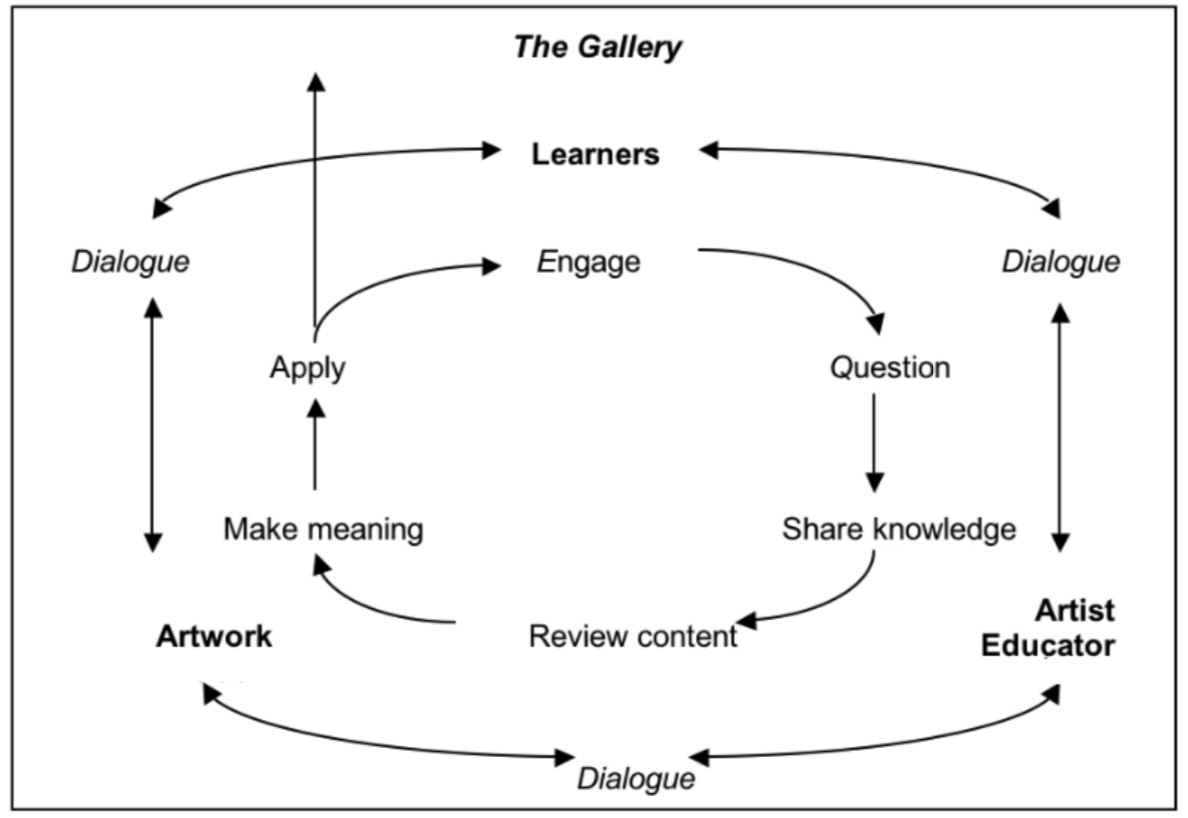

Dialogue between viewers (artist educators and learners) and artwork enables meanings to be generated through negotiation between knowledge embodied in the artwork and the experience and understandings of these viewers. (Pringle)

In this context, experiences of artwork can anchor the dialogue, and provide a new path for students to form connections. The experience of visiting an gallery can thus be a tool to support the development of a culture which enables students form learning from a community, and will be an essential part in the curriculum.

However, meaning making through the stimulus of artwork does not just have to occur from external sources. Sharing and responding to peers work as it progresses can also provide an opportunity to make use of the meaning making framework that Pringle has developed. There is a useful diagram which is included in the appendix for the process of learning from responding in gallery visits.

Developing choice from meaning making

By sharing and exploring the connections they make from community dialogues, students will be able to explore their own context and view.

‘And, in making claims about artworks, perhaps incorporating their features into their own practice, the student is experimenting with, trying out, taking on a kind of responsibility and authority, in that she now becomes responsible for those judgements and actions, those sayings and makings, and is open to being asked for reasons for them’ (Walton,)

By starting each unit with developing meaning making, learners will be able to take responsibility for their ideas, which will create a foundation for personal choices about how they will visually respond as artists.

Fluid and adaptable to change

Through the reading, one area has been repeatedly highlighted, and it is that art education is always in flux, as the subject itself is constantly evolving. The Ofsted research review notes that the ‘vastness, plurality and richness of the subject presents challenges to subject leaders’ (‘Research Review Series’), what art education is, and should address is a topic for debate and there is no one answer. With this in mind, I think the evolving nature of the subject needs to be addressed in the curriculum. As such, I will keep the actual document of the curriculum brief, and clarify that is a constant working document, that can and will be adapted as the implementation continues, and as student voice can shape the development, and advancements in the subject guide new methodologies for practice.

Dual Setting

The ASC will also consider developing the learning into the platform of teams, which is a resource that the school already has. This will enable the concepts in rhizomatic pedagogy to continue outside of the physical space in the classroom. As inspired by Cormier, the virtual space will be used for content sharing, and responding to peers developments. It is also creating an opportunity for taking responsibility, which also allows for the activation of the subjectification domain (Biesta).

‘The next level of responsibility is empowering students to work on their own to make their own contributions to the process. The more other students see knowledge negotiation happening from their peers, the better.’ (Cormier, Student Responsibility in a Collaborative Curriculum)

In a review of online learning in art education, a few areas to consider in forming this new curriculum have guided me. Sonvilla noted that online learning online teaching ‘creates more opportunities to de-emphasize the educator as the ‘authority’’(Hanrahan et al.), which will further emphasize the importance of students own ideas in the community. Working online allowed for new opportunities for collaboration, as some students were more comfortable with voices their views in this space (Raevaara in Hanrahan et al.), and that dual online learning environments were most effective when students were interested or invested in the subject matter (Sonvilla Hanrahan et al.)

The Art Scholars Curriculum

On the next pages, I will present the draft for the new curriculum, along with an outline for the first unit. The aforementioned concepts and underpinning theory has been considered in how this has been formed. The curriculum itself is a working document, and this is integral to it’s design.

Trinity Art Scholars curriculum

Intent: The Trinity art scholars programme is designed to build on the skills developed in lessons, and provide and opportunities for students to develop their practice as artists. To be an artist is to question, work together, develop creativity, and pursue topics that you are passionate about. This underpins the purpose of the art scholarship programme- is it so provide the space and creative community for the art scholars to explore their identity as an artist. As such, the Trinity art scholars will be termed as artists, and not students from this point in this intent statement.

Each term will have a theme that will act as a starting point. The aim is for the starting point to create an anchor for which to start individual or collective creative processes. As the community of the art scholars learns to work together, the art scholars programme themes will emerge from the students themselves, they will have the option to choose themes either individually or collectively important to them. An important aspect of this programme is working as a community, which will be enabled by the art teacher in specific tasks.

Art scholars club occurs on Monday lunch time, and Thursday afterschool from 3.15-4.00 pm. There is also a virtual space where contributions are encouraged.

Aims of the art scholars programme:

1. Develop a creative community of artists, where all can learn from each other and provide encouragement.

2. Learn how to develop personal creative choices in art, thus developing each individuals personality and style as an artist

3. Work on themes and topics interesting and relevant to the artists in the art scholars programme

4. Have fun! Enjoy making and creating art.

Processes of learning:

- Develop the use of a virtual space using Microsoft teams as an area to share and collaborate on ideas.

- Options to work individually or collaborate on creative tasks.

- Artists will determine the media, there will be opportunities to work with new materials and have new experiences

- Link to local, personal or collective knowledge. Artists can bring their own context and interests into their work, bringing links with faith, culture, and wider interests.

-First hand experiences of viewing and interacting with art will be facilitated at least once per term. This can take the form of a gallery visit, working from first hand sources, or external artist led workshop or talk.

Succes criteria for participants:

1. Participation is regular, and engagement is taking place in both the virtual and physical space.

2. Artists discuss and develop ideas both individually and as a community

3. Participation in collective tasks or decision making.

4. Artist feel greater confidence in making creative choices

Success Criteria of the curriculum

1. There is no ‘assessment’ of the work in the art scholars programme, this is a space for artists to develop their personal visual language.

2. Collaboration is often a new and challenging process. A success criteria for this programme is the completion of collaborative pieces, or a emergent

3. Student and key stakeholder views will guide the development of the art scholars programme, and as such will also be an indicator of the success of the curriculum, in both the individual progress and the group progress.

|

|

Michealmas Term 2023 |

Lent Term 2024 |

Trinity Term 2024 |

|||

|

|

M1 |

M2 |

L1 |

L2 |

T1 |

T2 |

|

Topic/tasks |

No specific unit, students completed a range of one of art activities. |

Prompt: ‘Trees’ Artists consider how to visually represent ‘trees’, and consider both abstract and representative approaches. |

In the last week, students to discuss the next ‘unit’- teacher to provide a ‘menu’ of ideas to support early decision making. |

Student determined theme. |

|

|

|

Collaboration |

Artists applied to be part of the art scholarship programme |

No collaboration occurred. |

Discussion and sharing of visual ideas. |

Artists take part in a collective mural, where each a |

Sharing of ideas and inspiration points. |

Possible collaborative task, or dialogue and peer feedback. |

|

External experience |

Trip to ‘Framed’ digital art experience |

External artist workshop from Dulwich picture gallery |

First hand drawing trip. |

Gallery visit to new venue. TBC. Artist voice to determine options. |

Trip to Dulwich Picture Gallery (Workshop already paid for) |

Celebration event, open to parents/carers of artist to view and celebrate work created in the academic year. |

|

Dual space |

This was not utilized. |

Sharing of visual resources on online space. |

Online: Students vote and discuss next unit. |

Sharing of visual resources on online space. |

Online: Students vote and discuss next unit. |

|

|

Art Pack requirement |

This was not utilized. |

Students receive art parks. |

Place bid for materials based on student voice. |

New material based on student voice. Pack develops cumulatively as needs develop. |

|

Timeline: (draft)

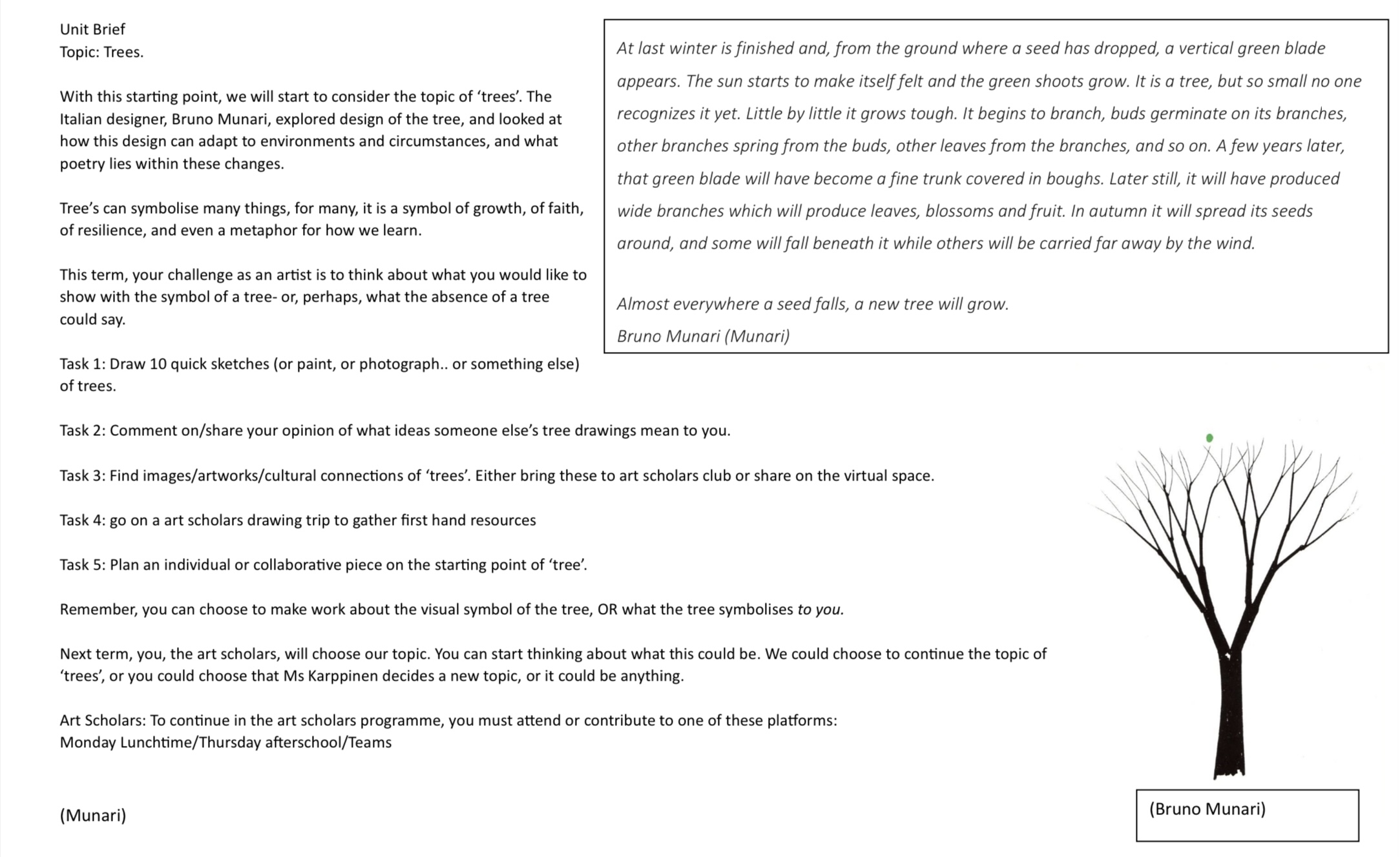

Unit Brief

Topic: Trees.

With this starting point, we will start to consider the topic of ‘trees’. The Italian designer, Bruno Munari, explored design of the tree, and looked at how this design can adapt to environments and circumstances, and what poetry lies within these changes.

Tree’s can symbolise many things, for many, it is a symbol of growth, of faith, of resilience, and even a metaphor for how we learn.

This term, your challenge as an artist is to think about what you would like to show with the symbol of a tree- or, perhaps, what the absence of a tree could say.

Task 1: Draw 10 quick sketches (or paint, or photograph.. or something else) of trees.

Task 2: Comment on/share your opinion of what ideas someone else’s tree drawings mean to you.

Task 3: Find images/artworks/cultural connections of ‘trees’. Either bring these to art scholars club or share on the virtual space.

Task 4: go on a art scholars drawing trip to gather first hand resources

Task 5: Plan an individual or collaborative piece on the starting point of ‘tree’.

Remember, you can choose to make work about the visual symbol of the tree, OR what the tree symbolises to you.

Next term, you, the art scholars, will choose our topic. You can start thinking about what this could be. We could choose to continue the topic of ‘trees’, or you could choose that Ms Karppinen decides a new topic, or it could be anything.

Art Scholars: To continue in the art scholars programme, you must attend or contribute to one of these platforms:

Monday Lunchtime/Thursday afterschool/Teams

(Munari)

Figure 3. Visual Prompt for the unit in the curriculum.

A personal note:

One area that has bothered me in writing this is the play of power dynamics, and the role of a teacher in creating a ‘creative’ community. There is a sense of supervision, that is antithetical to having a truly democratic social structure. I am aware of this challenge, and I need to note that this something I am in the process of understanding. For now, I have made my peace with the idea that I am showing students the experience of developing community, and learn from each other, and that as this programme continues, I can perhaps relinquish some of the power. This may be totally new as social structure. There is also an assumption that students want to have total agency, for some, in my experience, it is too much to be suddenly encountered. I want to create a space where students can make choices, even if it is as simple as the choice of choosing an option given by me, it is still a start.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Extract from Trinity art department handbook

Appendix 2

Figure 2: (Pringle) Meaning making framework in gallery settings.

Citations:

AQA. GCSE Art Specification. https://www.aqa.org.uk/subjects/art-and-design/gcse/art-and-design-8201-8206/specification-at-a-glance. Accessed 30 Dec. 2023.

Atkinson, Dennis. ‘A Critical Reading of the National Curriculum for Art in the Light of Contemporary Theories of Subjectivity’. Journal of Art & Design Education, vol. 18, no. 1, 1999, pp. 107–13. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5949.00161.

Biesta, Gert. Pragmatising the Curriculum: Bringing Knowledge Back into the Curriculum Conversation, but via Pragmatism - Biesta - 2014 - The Curriculum Journal - Wiley Online Library. https://bera-journals-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.libproxy.tuni.fi/doi/10.1080/09585176.2013.874954. Accessed 29 Dec. 2023.

---. ‘Risking Ourselves in Education: Qualification, Socialization, and Subjectification Revisited’. Educational Theory, vol. 70, no. 1, 2020, pp. 89–104. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12411.

Cormier, Dave. Rhizomatic Learning | Advance HE. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/rhizomatic-learning-0. Accessed 23 Dec. 2023.

---. Student Responsibility in a Collaborative Curriculum. ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub, https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/communityascurriculum/chapter/student-responsibility-in-a-collaborative-curriculum/. Accessed 29 Dec. 2023.

Hanrahan, Siún, et al. ‘`Interface: Virtual Environments in Art, Design and Education’: A Report on a Conference Exploring VLEs in Art and Design Education’. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, vol. 8, no. 1, Feb. 2009, pp. 99–128. SAGE Journals, https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022208098305.

Karppinen. Trinity Art Handbook.

Munari. Drawing a Tree. 1977.

‘National Curriculum in England: Art and Design Programmes of Study’. GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-art-and-design-programmes-of-study/national-curriculum-in-england-art-and-design-programmes-of-study. Accessed 27 Dec. 2023.

Owen Wilson, Leslie. ‘Types of Curriculum - Detailed Explanations of the Mutiple Types of Curriculm’. Https://Thesecondprinciple.Com, https://thesecondprinciple.com/instructional-design/types-of-curriculum/. Accessed 27 Dec. 2023.

Pringle, Emily. ‘The Artist-Led Pedagogic Process in the Contemporary Art Gallery: Developing a Meaning Making Framework’. International Journal of Art & Design Education, vol. 28, no. 2, 2009, pp. 174–82. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1476-8070.2009.01604.x.

‘Research Review Series: Art and Design’.GOV.UK, https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/research-review-series-art-and-design. Accessed 27 Dec. 2023.

Rosenshine, Barak. Principles of Instruction - UNESCO Digital Library. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000190652. Accessed 29 Dec. 2023.

Siemens, George. Connectivism: A Learning Theory for the Digital Age. https://itdl.org/Journal/Jan_05/article01.htm. Accessed 23 Dec. 2023.

Trinity School. Trinity Curriculum Handbook. 2020.

Walton, Neil. ‘Anton Ehrenzweig, the Artist Teacher and a Psychoanalytic Approach to School Art Education’. International Journal of Art & Design Education, vol. 38, no. 4, 2019, pp. 832–39. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12279.

---. ‘Making Art Explicit: Knowledge, Reason and Art History in the Art and Design Curriculum’. International Journal of Art & Design Education, vol. 42, no. 4, 2023, pp. 574–83. Wiley Online Library, https://doi.org/10.1111/jade.12477.

Other reading that has contributed

Smith, M. K. (1996, 2000) ‘Curriculum theory and practice’ The encyclopedia of pedagogy and informal education, www.infed.org/biblio/b-curric.htm.

Szpakowski, M. (2019), On Art and Knowledge. Int J Art Des Educ, 38: 7-17. https://doi-org.libproxy.tuni.fi/10.1111/jade.12179